The largest genetic map of cancer in cats opens the door to treatments shared with humans

‘It seemed deeply unfair that in this era of precision medicine, where targeted therapies are the treatment of choice for cancer in humans, they didn’t exist for cats,’ says the senior author of the study

Cats, along with dogs, are the animals that spend the most time with humans. They share spaces, routines, and even illnesses. They are exposed to almost all the same environmental stressors that induce tumors in people. However, unlike what happens with dogs, cancer research in felines is very limited. Now, a huge study published in Science, using hundreds of tumor samples, has obtained the most complete oncogenome of the domestic cat. Among its findings, two are closely related: cats and humans suffer from almost the same types of cancer, and this opens the door for the possibility that advances in the fight against cancer in one species could be applied to the other.

“Cancer is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in older cats. However, very little is known about the genetics that drive these cancers,” notes Louise van der Weyden, a researcher at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the U.K. And senior author of a study that analyzed tumor samples (and adjacent healthy tissue) from 493 cats. “It seemed deeply unfair to us that in this era of precision medicine, where targeted therapies are the treatment of choice for cancer in humans, they didn’t exist for cats,” adds Van der Weyden. Needing to know the genetic mutation behind each tumor in order to design effective treatments, “we set out to characterize the genes that drive cancer in cats, defining the oncogenome of the domestic cat,” explains the geneticist.

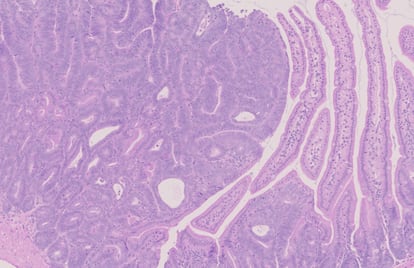

With the participation of around 20 institutions, a large group of geneticists, oncologists, and veterinarians sequenced 978 genes related to the tumors found in these cats. These genes have a sequence and function similar to approximately 1,000 genes involved in human cancer. In total, they collected tissue samples from 13 major tumor types, ranging from osteosarcoma to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and including various mammary carcinomas. These samples came from biopsies and necropsies of domestic cats, the vast majority of which were mixed breed, from five countries.

Mutation by mutation, gene by gene, and tumor by tumor, what they have discovered is the striking resemblance between cats and humans. “What initially surprised us was the degree of overlap in the mutated genes in cancers of both species,” Van der Weyden explains in an email. “However, in essence, it is probably not so surprising when you consider that human and feline genomes are remarkably similar,” she adds. Approximately 90% of the genes in domestic cats are homologous to those in humans, more than those in dogs or mice.

Breast cancer is a good example. The study identified seven specific genes that lead to the development of certain types of aggressive breast cancer. The most common driver gene is FBXW7. More than half of the tumors in cats have mutations in this gene. “One subtype is so-called triple-negative breast cancer, which is particularly aggressive and more common in young women,” Van der Weyden points out. Cats contract this subtype of breast cancer much more frequently than humans. “In cats, it is extremely aggressive and resembles triple-negative breast cancer in women,” the researcher adds.

The similarity in breast cancers opens the door to collaboration between different species in medicine. “We discovered that the FBXW7 gene commonly mutated in feline breast cancer, and that cancer cells carrying mutations in FBXW7 were more sensitive to vinca alkaloids,” says Van der Weyden. She is referring to compounds derived from this plant, sometimes called periwinkle in English, that are used in chemotherapy. This means that these drugs used in humans could be used in cats.

They also observed similarities with human driver mutations for lymphomas, bone tumors, lung cancer, skin cancer, and central nervous system tumors, such as meningiomas. Based on this, future research could generate new knowledge and therapies for both species. This would align with the concept of One Health/Medicine, a holistic approach to disease that extends beyond the human species.

“It’s an approach that Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur [the fathers of microbiology and modern medicine] had already embraced, but we’ve become arrogant, even though our tuberculosis is also that of cows. What about SARS-CoV-2 or the flu virus that affects birds, mammals…?” Recalls Alejandro Suárez Bonnet, a professor specializing in comparative pathology at the Royal Veterinary College in the U.K. And co-author of this feline oncogenome. The researcher argues that domestic animals share so much with humans that they could be better models than laboratory mice. “Virtually all types of tumors that develop in humans also develop in dogs,” he says, and, as they now demonstrate, also in cats.

The standard practice in cancer research begins by inducing tumors in mice. This already introduces a bias. “There are cancers that are very difficult to develop in the laboratory because they don’t replicate exactly,” says Suárez, who is also a pathologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London. “We have identified groups of tumors that can represent spontaneous models of human tumors, so there is a benefit in the direction of human research,” he adds. And he gives a specific example: “Canine bladder cancer, which is also very aggressive, is biologically very similar to human bladder cancer.” One of the contributions of this work on cancer in cats is that it demonstrates “the importance of veterinary medicine and domestic animals as a fundamental element in general biomedical research,” Suárez concludes.

“This study reinforces the value of companion animals as natural models for comparative oncology and for the development of precision medicine strategies,” adds Guadalupe Sabio, a researcher at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO). Sabio, who was not involved in this research, believes that the most interesting aspect is not the genomic description itself, but what it implies: “In human medicine, we have seen for years that close collaboration between clinicians and basic researchers has been fundamental to advancing cancer research, but in veterinary medicine, these kinds of bridges are still less developed.”

Now there’s a context that could change this, with more and more pets living longer and spontaneously developing cancer in environments shared with people. For Sabio, director of the metabolic interactions group at the CNIO, this makes these patients enormously valuable from a scientific point of view. If these bridges are strengthened, the scientist concludes, “the benefit can clearly be bidirectional, for both human and veterinary medicine.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.