Albania, Europe’s laboratory where AI combats (or hides) corruption

Following the government’s announcement that a virtual minister will control public contracts, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is investigating its creators and the deputy prime minister

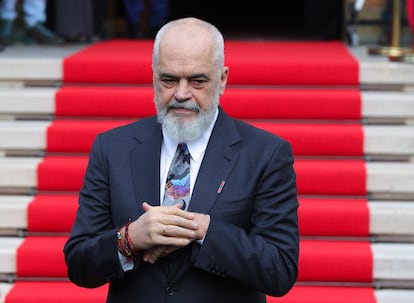

Albania’s prime minister, Edi Rama, knows how to draw attention to his country. The former national basketball player (who stands at 6′6″) introduced Diella, a virtual minister in charge of public procurement, last September. The leader of the Albanian Socialist Party, who has been in office for over 12 years and is now serving his fourth term, won the 2025 elections promising Albania’s full EU membership by 2030. To achieve this goal, combating corruption is essential, one of Brussels’ major demands of the country of 2.3 million inhabitants, which formally began EU accession negotiations four years ago.

Presenting the initiative, Rama clarified: “We are not delegating [to Diella] the responsibility of governing or making final decisions. We are giving her the responsibility of doing what she does best: processing data quickly and giving us very fast answers […] Public tenders will be 100% free of corruption."

The opposition asked members of the Socialist Party in government: “Who will the police arrest if this minister makes a mistake or facilitates fraud? The programmer?” Diella, whose name means “Sun” in Albanian, responded to some of the criticism from her screen in parliament: “Unlike humans, I have no relatives to favor, no friends to award contracts to, and no emotions to cloud my judgment about public data. My loyalty is mathematical.”

Rama, 61, argued: “Technology has no friends, doesn’t accept coffee, and isn’t afraid of retaliation.” He maintained that the algorithm will overcome the country’s “structural nepotism.” “We are a country of cousins — it’s not easy to have totally fair and transparent interactions in a country of cousins,” he said in an interview with The New York Times in January.

International media reported on the appointment of Minister Diella. But many Albanians expressed their distrust. Among them was Jorida Tabaku, a member of parliament for the Democratic Party and chair of the EU Affairs Committee. “If the system deploying these tools lacks integrity, AI risks becoming a black box that centralizes power instead of exposing abuses,” she stated in an email.

Just two months after Diella was appointed to the Cabinet, the Special Prosecutor’s Office against Corruption and Organized Crime (SPAK) requested the suspension of a key figure in Rama’s government: Deputy Prime Minister Belinda Balluku. The Prosecutor’s Office accused her of “violating equality in public tenders.” The case went to the Constitutional Court, which on February 6 disqualified her from holding office. Rama criticized the ruling and refuses to allow parliament to lift the immunity of his right-hand woman, who is also minister of Infrastructure and Energy.

Meanwhile, Albanian skepticism toward artificial intelligence turned to outrage when SPAK placed the designers of Diella under house arrest: Mirlinda Karçanaj, the director of the National Agency for the Information Society (AKSHI) — the body that manages the state’s digital infrastructure — and her deputy, Hava Delibashi. Six other people were also charged with corruption, including a deputy police chief and three businessmen. The case against them includes accusations ranging from rigging public tenders to kidnapping and intimidating tech entrepreneur Gerond Meçe to force him to withdraw from a public procurement process.

In this context, on January 24, several opposition parties called for protests that culminated in Molotov cocktails being thrown at the prime minister’s office. The demonstrations, spearheaded by the Democratic Party, continued on February 10 and 11 outside Rama’s office, demanding his resignation. Meanwhile, actress Anila Bisha, whose likeness and voice served as the basis for the avatar’s design, has sued the government for the unauthorized use of her image.

“Pure propaganda”

Gazment Bardhi, head of the Democratic Party’s parliamentary group, described the virtual minister as “pure propaganda” in a phone interview. “Those who created Diella are officially accused of corruption, kidnapping, and violating bidding rules. Did they really intend to fight corruption?” He asked. SPAK has charged the deputy prime minister in connection with 11 contracts worth €1.1 billion. “In a corrupt government, no algorithm can solve the problem,” he argued.

Distrust of the government’s good intentions extends beyond the opposition parties. Azmer Duleviç, an engineer and independent activist, attended the January protests with a sign that read: “The fish’s head is rotten: corruption starts at the top.” Speaking from Tirana, he added: “AI is no panacea. Its credibility depends on clean data, impartial oversight, and genuine political will.”

This newspaper has tried to obtain a statement from the Rama government, but has received no response.

Andi Hoxhaj, a Western Balkans law expert at King’s College London, points out that Diella aims to detect and prevent irregularities among companies participating in public tenders and to determine whether they meet the requirements to bid. “This must be the perspective from which any evaluation is made,” Hoxhaj warns. The professor emphasizes that “it is too early to make a proper assessment of Diella. It hasn’t even been a year yet.”

Hoxhaj clarifies that SPAK is the institution responsible for investigating high-level corruption cases since 2019. He adds that this body has been fundamental in combating high-level corruption since its creation, inspired by the special anti-corruption prosecutor’s offices in Croatia and Romania. However, the expert emphasizes that the government “must implement more anti-corruption policies to ensure effective preventative measures are in place.”

Rovena Sulstarova, manager of the Governance Program in Albania at the Institute for Democracy and Mediation (IDM), believes that the impact of artificial intelligence in the fight against corruption is, for now, “mixed.” In her view, AI can strengthen transparency and limit opportunities for abuse. But she warns that it is not a solution on its own. “It shouldn’t be overestimated.”

The 74-year-old intellectual and writer Fatos Lubonja is deeply skeptical about Rama’s intentions, and even those of the EU. Lubonja spent 17 years in prison under Enver Hoxha’s communist dictatorship (1944-1985). Today, speaking via videoconference from Tirana, he explains that Rama is like a chair supported by four legs. “One is the oligarchs, all the wealthy people who surround him. Another is the media they own or finance. The third is organized crime. And the fourth is international support, especially from Western Europe and the U.S.”

The writer explains that Albania has always based its relationship with various empires on two factors: vassalage and its peripheral status. “Vassals needed legitimacy from the center of the empire. In return, the center turned a blind eye to what was happening here. This worked with the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Soviet Union… And now with the EU and the U.S. Rama needs this legitimacy from the West. And he has known how to give the West what it wants, such as the agreement with Giorgia Meloni on migrants, whereby Albania hosts refugees sent by the Italian government in internment camps.”

Lubonja believes that the EU ambassadors in Albania are well aware of the country’s reality. “I’ve spoken with the German, the Dutch, the Polish ambassadors… It’s true that they are very concerned about organized crime and that they support SPAK. But Albania is complicated. And Rama knows how to play both sides.” Lubonja believes that there is a certain sense of superiority in the European view of Albania. “Deep down, in Brussels, they think we don’t deserve a democracy and that we need a kind of prince like Saudi Mohammed bin Salman. It’s easier for them to deal with someone like that.”

Ultimately, cleansing the upper echelons will depend on human will. Lubonja concludes: “I don’t believe SPAK alone can change the country. You can’t reform the justice system alone when politics, the economy, and organized crime are all moving in the opposite direction. And Rama is not acting in good faith.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.