Richard Linklater: ‘Film and rock were the fundamental passions of my generation. I don’t know if that’s still the case today’

The director of ‘Before Sunrise’ and ‘Boyhood’ is a leading figure in American independent cinema. His latest film, ‘Nouvelle Vague,’ was released in late-2025 and is a tribute to Godard, one of his idols

“Are you also going to ask me about Donald Trump?” Richard inquires. He says this with a knowing smile as soon as he sits down, after the ritual exchange of greetings. “Please don’t. Your colleagues have already done so. I have an opinion on the matter, but it’s trivial. I’m a filmmaker, not a political scientist.” “As a citizen,” he continues, “I’m concerned about the deterioration of our democracies, but I have nothing substantial to add about that individual. I trust that Trump will leave sooner or later and that another president will come along to try to fix what he’s broken. That’s all I can say,” he shrugs. “So, let’s talk about film instead.”

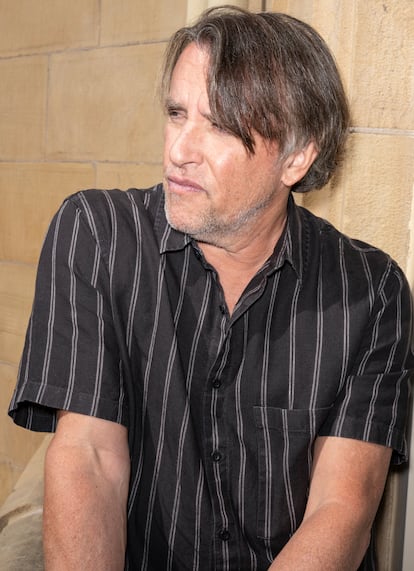

The invitation can’t be ignored. Linklater — born in Houston, Texas, 65 years ago — is enthusiastic when it comes to talking about film. He has dedicated the last four decades of his life to this profession. It was also the main passion in his youth, along with reading, baseball and American football.

According to Linklater, film became his guiding light the day he invested his savings in a Kodak Super 8 camera and embarked on the adventure of filming in the streets of the university town of Austin. Before that, he wrote screenplays, played a lot of sports and worked on an oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico. However, none of these alternative life projects could compete with the “excitement” of trying to make films like his heroes: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, Welles, Scorsese, or Fassbinder. From that impulse came his most important works, such as Slacker (1990), Dazed and Confused (1993), Before Sunrise (1995), A Scanner Darkly (2006) and Boyhood (2014), which are among the best movies that American independent cinema has produced in recent decades.

Linklater met with EL PAÍS during the recent San Sebastián Film Festival. He came to speak to the press about his latest film, Nouvelle Vague (2025), but he ended up spending quite a bit of time answering questions about Trump (tariffs, deportations, threats to freedom of expression) and “apologizing for being American.” It’s all part of the job, he admits; politics seems to interest everyone these days, while cinema — especially cinéma d’auteur, which is demanding and driven by intellectual concerns — is on its way to becoming a dead language.

“I reflect on this very often. Cinema, along with rock music, was one of the fundamental passions of my generation, those of us who were young in the mid-1980s. I don’t know if it’s still as essential for my children’s generation… I don’t think so. Today, cinema competes with many other stimuli, many other screens, as well as a host of banal alternatives to which we can dedicate our time.”

That is, in part, the reason why he embarked on the “suicidal” undertaking of filming Nouvelle Vague. It’s a witty and meticulous chronicle, shot in exquisite black and white, about the making of a legendary film — Breathless (1960) — by Jean-Luc Godard. “It stems from the desire to give back to cinema at least some of what it has given me,” he explains. “The story of that shoot in Paris, in the summer of 1959, is interesting and not widely-known. I wanted to tell it to young film lovers, to share with them my enthusiasm for what the 29-year-old Godard did, which was, basically, to break all the rules, even those dictated by common sense, in order to reinvent and rejuvenate cinema.”

Question. At what age and under what circumstances did you first see Breathless?

Answer. It was before I turned 20, in Austin, when I was starting to work in film. My father recommended that I see it. He told me it was a rather peculiar film, but a classic.

Q. Do you remember your first impression?

A. It puzzled me, yes. And it intrigued me. Formal aspects caught my attention: its originality, its lightness, its elegance. But I wasn’t yet able to fully process it, to understand how unique and relevant that film was, to what extent it was a radical break with almost everything that came before it. It ushered in a new era, like the emergence of punk in the music world. Over the years, I’ve rediscovered it. And it fascinates me more and more each time.

Q. Would you say that it’s one of your favorite films?

A. There are so many! But I love this one. And Godard is an intellectual hero to me, an example of the [right] attitude toward life and cinema. I think the fundamental lesson he gave to other filmmakers is that there’s always a different, more personal and less conventional way of doing things. I try to keep that in mind, although Godard raised the bar for innovation incredibly high. It’s very difficult to live up to his standards.

Q. It’s often said that many music fans are followers of either John Lennon or Paul McCartney. In film, something similar could be said about the two main directors associated with the French New Wave: Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut, the Martian and the Earthling. Are you more of a Godard or a Truffaut fan?

A. Interesting. I’d say that, on a normal day, I’d choose the Earthling. I connect a lot with Truffaut; his films feel intimate and close to me. But Godard… well, Godard is cinematic hard drugs. His films can be admired, but not imitated; to make anything remotely similar, one would have to be inside his mind.

Q. In a way, I think Nouvelle Vague is similar to the kind of film about Godard that someone like Truffaut might have made.

A. Really? I understand what you mean, but I’m not sure I entirely agree. I think if Truffaut had made a film about Godard, it would have been very intimate because he knew him very well, but a certain degree of resentment would have crept into it. They were friends, but they drifted apart. And Truffaut died before they could fully reconcile, as I believe happened, incidentally, with Lennon and McCartney.

Linklater is very clear about what was exceptional about the filming of Breathless (1960): “Everything,” he affirms. “To begin with, it was fertile chaos, an organizational disaster, managed somewhat frivolously by a very talented but inexperienced director.” Furthermore, to reinforce this high degree of creative dissonance, the movie “had the presence of an American actress, Jean Seberg, who wasn’t a big star but almost, and who didn’t have the slightest idea about what she was getting herself into.”

According to Linklater, Seberg came to detest Godard, but she did so cordially. “And no other director ever made such good use of her beauty, her charisma and her talent,” he emphasizes. Then, there’s the “eccentric, youthful, adventure” aspect of the whole thing: “The lack of a real script; Godard’s whims, which baffled the actors and the crew; the attitude of the other protagonist, Jean-Paul Belmondo, who also wasn’t entirely sure what they were doing, but was receptive and docile and he left as a pop culture icon, although it took him a long time to realize it.”

Linklater filmed Nouvelle Vague as if it were the making of a movie he reveres, while subtly bringing it closer to contemporary sensibilities. We asked him about his favorite scene from Breathless, and he chose the one that nine out of 10 cinephiles steeped in the cult of vintage modernity would pick: the stroll down the Champs-Élysées, when Seberg is selling copies of The New York Herald Tribune. Belmondo chats with her and the camera follows them.

Despite everything, he believes there are many other films that are just as legendary and crucial to the evolution of cinema: “Something I was very mindful of was not filming the scenes the way Godard did,” he adds. “The point of view is different: mine, that of an external observer, trying to show the action from a different angle.”

How are they reacting in France to an American director — who doesn’t speak their language — tackling such a French story? Linklater responds that, if anyone is accusing him of cultural appropriation, he has no knowledge of it: “I think French critics, in general, have appreciated my approach to their film culture being both fascinated and respectful. Breathless is also the chronicle of a benign cultural clash between Godard and Seberg, between the French New Wave and Hollywood. And the result of that clash is plain to see… and it’s extraordinary. Furthermore, the French consider Godard to be part of humanity’s heritage. They’re accustomed to exporting their culture; they don’t feel the need to keep it all to themselves.”

The proof is that many of the accomplices he found when he decided to embark on this project were, in fact, French. “I couldn’t have done it without them. It had to be my French film, shot in Paris, in French, with mostly French partners, screenwriters and actors. It wouldn’t have made much sense to approach it any other way. At least, not for me.”

It must have been difficult to find 100% American investors for such a project, which is so European and so auteur-driven. “I’m incredibly lucky that, every time I conceive of a crazy project — with dubious commercial viability — I find someone willing to jump off the cliff with me," the director chuckles. “This time, the partners willing to back me up in another of my suicidal projects were in France.”

Linklater, despite everything, usually emerges quite unscathed from his commercial suicides. It’s a constant in his career ever since he invested $23,000 of his own money in Slacker (1990), which ended up grossing over a million bucks. “That was an optimal way to get into the business. I’ve had the opportunity to make films within the system, with big budgets, like Bad News Bears (2005) or School of Rock (2003), but if my career has taught me anything, it’s that commercial risk and artistic risk are usually interconnected. The cheaper the film, the more freedom, creative control, and opportunity to take narrative and aesthetic risks you will have. In the French New Wave, the financial risk is moderate, so I haven’t suffered any massive pressure or creative interference of any kind.”

Q. It’s a very ensemble film. It features some of the biggest names in film history as supporting characters, from Truffaut to Roberto Rossellini, as well as Agnès Varda, Jacques Rivette, Jean Cocteau… it’s a feast for cinephiles.

A. Yes. We shoehorned some of them in, because we admire them and wanted them to be in the film. That’s the case with director Robert Bresson, one of my heroes. We discovered that he was also shooting a film in Paris that summer [of 1959]: we imagined an encounter on the metro where Bresson — a very peculiar fellow — treats Godard with gentle condescension.

Q. Of all those illustrious figures in Godard’s circle, which one do you think deserved a film about their life?

A. [Agnès] Varda, for example. She was the mother of the French New Wave, making modern, transcendent films in France long before the label was even invented. And she was an extraordinary woman who made great films well into her eighties. But at the time, Varda and her husband, Jacques Demy, were very much on the periphery of Godard’s world, so they only appear in a couple of scenes. Truffaut and the filming of The 400 Blows (1959) — the other great manifesto of French cinema from the late-1950s — would also make a good film.

Q. In your movie, Roberto Rossellini is portrayed as a kind of hustler who attends a tribute event in Paris, only to take entire trays of canapés back to his hotel.

A. Yes. And I know that particular scene has caused a stir in Italy. But it’s just a wink, a knowing joke. As the Rossellini in the film says: “You young French people have stolen everything from my cinema, so I’m going to take your canapés.” It’s an act of poetic justice.

Q. Were you obsessed with making the characters and actors resemble the real people as closely as possible?

A. Not really. Guillaume Marbeck’s Godard isn’t the real Godard, and Zoey Deutch’s Seberg isn’t the real Seberg. I gave them the freedom to develop their characters in a way that was consistent with the script, without having to stiffly imitate their models. I insisted to Adrien Rouyard that I wanted him to portray Truffaut as an optimistic and cheerful man, but he had seen a lot of footage of the real Truffaut and found him rather reflective and melancholic. So, I told him: “Your character is 27-years-old and has the best job in the world — that of a film director. And he’s very good at what he does. Don’t you think he has plenty of reasons to be happy?”

Q. What do you think Jean-Luc Godard would have thought of this film?

A. I don’t know. He was a very reclusive and demanding man; most of his opinions about other directors’ films were pretty negative. But I do think he would have appreciated that my film shows him at a moment of fulfillment, when he was shooting the first of his masterpieces and had his whole life ahead of him.

Q. And what do you think Donald Trump would have thought of Nouvelle Vague?

A. I imagine he’d be yawning from the very first scene. From the little I know of him, I don’t think this is the kind of film he’d be interested in.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.