Venezuela gives the green light for foreign capital to enter the oil sector

The government has created the necessary legal framework to privatize the industry, as Trump requested. The United States has lifted restrictions on crude trade with the Caribbean nation and resumed commercial flights

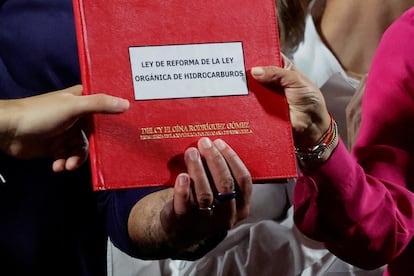

Venezuela’s National Assembly, controlled by the Chavista regime, has approved the reform of the hydrocarbons law, opening the oil sector to privatization. The debate on the law was swift, as demanded by the United States, and comes after the January 3 military strikes on Venezuelan territory and the capture of Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores. Since then, Washington has almost fully restored commercial relations with the South American country, once viewed as a source of instability and threats.

“Today is a historic day for the Republic, because despite the adversities, we have been able to maintain our oil industry,” said Jorge Rodríguez, the president of the National Assembly, at the end of the session. “By upholding the principles of sovereignty and independence, and the Republic’s ownership of its oil fields, we will make the sector more competitive by allowing the contracting of both national and foreign companies.”

The newly recalibrated relationship between Washington and Caracas — now shaped by oil — required this revised law to provide stronger guarantees for the investments President Donald Trump has said he is interested in making in Venezuela, where he is also seeking to edge out Chavismo’s partners, including Russia and China.

News of the reform’s approval in the Chavista‑controlled National Assembly was met in Washington with the U.S. Treasury Department’s issuance of General License 46, authorizing transactions with the Venezuelan government and state‑owned oil company PDVSA involving “the lifting, exportation, reexportation, sale, resale, supply, storage, marketing, purchase, delivery, or transportation of Venezuelan origin oil, including the refining of such oil, by an established U.S. Entity.”

As a parallel step to opening the industry to U.S. Capital, restrictions on air travel to Venezuela were also lifted on Thursday, meaning direct flights between the two countries will be resumed after more than seven years.

Previous licenses were narrowly tailored to specific companies authorized to conduct transactions with PDVSA, as in the case of the one that allowed U.S.‑based Chevron to operate. The new license is far broader, permitting operations by any “established U.S. Entity.” It does, however, prohibit transactions involving individuals or entities from Russia, Iran, North Korea, or Cuba. No expiration date is specified, but its validity depends on companies submitting regular reports within 10 days of their first transaction.

The new law, meanwhile, opens the door for private companies to enter the sector through direct contracts with PDVSA. Before the reform, foreign capital could only participate in Venezuelan oil production through joint ventures in which the government — which during the early years of Chavismo championed oil nationalism — retained majority ownership and operational control. This structure complied with the Venezuelan Constitution, which reserves oil activity and other strategic industries for the state. Those joint ventures required approval from the National Assembly. Under the new framework, direct contracts with private firms need only be reported. The law nonetheless specifies that the state will remain the owner of the oil fields where private companies carry out extraction activities.

Other specific changes focus on the commercialization of crude. Previously, only PDVSA was allowed to handle sales. Now, private companies may engage in “direct commercialization” and manage revenues through bank accounts abroad. Royalties — the payments owed to the state for the right to extract oil — are capped at 30%, a figure the executive branch may adjust at its discretion. An earlier draft of the reform had lowered royalties to 20% for direct contracts and 15% for joint ventures. The new framework also grants broad tax exemptions to companies investing in the sector.

The reform also includes a clause allowing disputes to be resolved through arbitration and mediation — a departure from the previous requirement that all conflicts be handled exclusively in Venezuelan courts, which lack judicial independence, as also stipulated in the Constitution. The measure is designed to ease investor concerns after past losses caused by expropriations carried out by Chavista governments.

The minority opposition bloc had called for a broader debate on the reform that deregulates the oil sector to favor private operations — a condition Trump set after the military strikes as a way to secure the political survival of the Chavista leadership now governing Venezuela without Maduro. Public consultation lasted only three days, during which interim President Delcy Rodríguez met first with industry workers and then with executives from oil companies interested in continuing business with PDVSA, including Spain’s Repsol, the U.S.‑based Chevron, and the U.K.’s Shell.

In less than a month, a basic legal framework has been assembled for this new commercial phase between the two countries. The final green light had already come from U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Wednesday: “Authorities there [in Venezuela] deserve some credit. They have passed a new hydrocarbons law that essentially eliminates many of the restrictions imposed during the Chávez era on private investment in the oil industry.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.