From the Bay of Pigs to the capture of Maduro: Over half a century of waiting for the fall of Castroism

Since 1960, Cuban exiles have been hoping to return to their homeland under a change of government. Some believe that now is the moment that outcome has been closest

The players at Domino Park must abide by certain rules that have been respected for years: speak softly, don’t carry alcoholic beverages, don’t arrive in flip-flops, and be a Miami resident no younger than 55. No one can explain why that’s the age limit, but it offers certain internal guarantees to the players: they won’t sit with novices or enthusiastic tourists visiting Calle Ocho, the heart of the disapora in Miami, to admire the nostalgic murals of Cuban exile, but rather be able to play one-on-one with their own kind, those who know Little Havana, people who left Cuba and helped build a city on “the swamp that was Miami,” who spend long hours thinking about what a return would be like and who never stop talking about politics. During a strange, cold January afternoon, almost a month after Nicolás Maduro’s capture, the players at the table wondered at what stage the Cuban regime had come closest to disappearing.

“When the Socialist Bloc fell, losing its economic support, what a blow that was!” Says Flavio César Crombet, 60, a law graduate from Cuba, whom Lázaro Jordás, a 79-year-old former engineer, interrupts to contradict. “No way, the worst moment is now with Maduro, and if Mexico cuts off their oil, Cuba will be finished in five days.” A third player remains silent, but a fourth, Raimundo Escarrás, an 82-year-old former merchant, believes that if the Cuban government ever falls, none of them will be alive to see it. “In the end, the United States has never wanted to bring it down, and both at the Bay of Pigs and now, the Cuban people have always been with the Castros.” Crombet steps in to correct him: “Back then, yes, but now there are no Castros left.” Then he makes a prophecy: “Remember this, if Trump invades, it will be in April, around the same time as the Bay of Pigs invasion.”

A few blocks from the domino table, after passing a hair salon, a supermarket, and several restaurants that offer mojitos and roast pork, is the Cuban Memory Park, where the monument to the Bay of Pigs invasion — or the attack on Playa Girón — stands in black marble, with an eternal flame that honors the more than 100 exiles who died during the invasion of April 1961, the first attempt to remove the Castros from power.

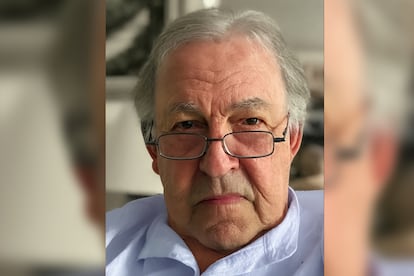

Only two years after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Tony Costa showed up at an office in Miami to enroll in Brigade 2506, a group made up of some 1,600 men, some of them young workers or students who trained in the backyards of houses in the Southwest, with support from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the goal of landing at Girón to “liberate Cuba.”

Costa first fought against the dictator Fulgencio Batista, burning tires and protesting in the streets of Pinar del Río, and he didn’t hesitate to support the guerrillas in 1959. “Castro presented himself as a democratic alternative,” he says in his elegant house in the upscale Coral Gables neighborhood. A short time later, he and his father sensed that things weren’t going well with Fidel, who had begun to attack private property, a measure that directly harmed them, a family of farmers who owned hundreds of acres of land where they grew tomatoes to sell to their main market: the United States.

Back then, Costa visited Miami from Cuba as if they were one and the same. He and his father would take a ferry and disembark hours later in Key West. He spoke English and was sent to study at the University of Florida. After the Revolution, the family knew they had to leave the island for good. They moved to Florida, bought land in Homestead, planted tomatoes, and then ventured into ornamental plants, eventually establishing Costa Farms, the largest nursery in the country, with more than 1,500 varieties cultivated on some 5,200 acres. The desire to return to Cuba, however, remained.

In April 1961, he felt ready to join the invasion. “We said, ‘We have to fight, we have to liberate Cuba, we can’t let communism take it over.’” He was 21 years old. A group from Brigade 2506 was transferred to Guatemala and Nicaragua, from where they would travel to Cuba. Due to strategic decisions, Costa would arrive later. On April 15, several planes began attacking airports on the island. Two days later, the members of the Brigade arrived armed. But after 72 hours, the Cuban counteroffensive, which resulted in 176 casualties, repelled the invasion. Even today, the exiles blame the failure on U.S. President John F. Kennedy, who did not provide them with the air support they needed. “He was a novice president, who inherited from Eisenhower the idea of eliminating Castro, but that wasn’t his plan. From then on, we’ve been paying for that failure, because at that moment, communism in Cuba could have been eradicated.” It was around that time that Fidel declared the “socialist and Marxist” character of his Revolution.

Costa was never able to join the invasion, and although the memory of so many fallen comrades is a grief he still carries, he says he has felt moved again these past few days. He doesn’t believe the closest the Castro regime came to defeating itself was at the Bay of Pigs, but rather now. “I’ve been waiting for this for over 60 years,” he asserts. “Things are serious now. It’s a moment of optimism and immediacy. We have the right people in this government to implement the policies. I’ve postponed death until Cuba is liberated.”

“How long am I going to wait?”

If there’s one thing Arnaldo Iglesias regrets, now that he’s 88, it’s not having been able to join the Bay of Pigs invasion, because by the time he found out, they were no longer recruiting. After the defeat, however, he became involved in Operation Mongoose, another CIA-funded attempt to overthrow the Castro regime. Iglesias was one of those responsible for the burning of the Pilón sugar mill in Matanzas, one of the many actions they carried out to destabilize the government on the island. He left Cuba in 1960, always with the idea of returning. “I’ve been waiting for 67 years, and there comes a point when you say, ‘How long am I going to wait?’”

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Iglesias joined the organization Brothers to the Rescue, which, with the help of exiles and the U.S. Coast Guard, carried out search and rescue operations in the Florida Straits to assist those who darted across the sea from Cuba. They threw them walkie-talkies, dry clothes, or bottles of water to alleviate dehydration, and alerted the authorities for rescue. “I literally saw sharks devouring rafters,” he recounts.

They also used to drop leaflets north of Havana. They calculated the distance, the altitude, and how the winds behaved, and released messages into the air containing articles from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “Castro accused us of subversive propaganda,” he says.

But the event that divided Iglesias’s life in two was the downing of two Brothers to the Rescue planes on February 24, 1996, by missiles fired by the Cuban Air Force, because they allegedly violated its airspace. Four Cubans died in the attack. Iglesias, a survivor, doesn’t know how his plane remained undamaged.

Now that Cubans have regained hope of reclaiming Cuba, Iglesias remains somewhat skeptical. The capture of Maduro, he says, “doesn’t necessarily” mean the end of Castroism. “They aren’t liberating Venezuela to benefit Venezuelans, but because it suits the United States, just as they haven’t been interested in Cuba disappearing for over 60 years.” Despite this, a change of government in his country is what he hopes to see before he dies: “My roots are here, my children, my grandchildren, but mentally I’m still just passing through. I want the best for Cuba, even though I won’t be able to enjoy it anymore, because the Cuba I long for no longer exists.”

Economic collapse

In 1962, Cuba found itself in the most dangerous position on the Cold War chessboard. Havana was at the heart of the conflict between the United States and Russia when the Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis, erupted. It was widely feared that Washington would attack Cuba, but it did not. Countless efforts have since been made to end the longest-running dictatorship in the Western Hemisphere.

Reinol Rodríguez, the military leader of the anti-Castro group Alpha 66, arrived in the United States in 1961 and returned three years later, dressed in olive-green uniform and rifle in hand, with ammunition to equip the counterrevolution rising up in the Escambray Mountains, a mountain range in the center of the island. Today, he still keeps his uniform and boots ready in Miami in case he needs to go and fight in Cuba. “My profession has been fighting for my homeland, all the time,” he says at 85 years old. “If not now, it will never be, because there is a president who ousted Maduro from Venezuela, and there is Marco Rubio. There is hope like never before.”

Over the years, there have been many other attempts to destabilize the regime in Cuba, but Castroism remains. “For decades, the United States did not invade Cuba because of the high cost of a war both on and off the island, in the midst of the Cold War. Now, it does not invade because the costs would outweigh the benefits in any intervention scheme,” asserts historian Rafael Rojas, author of the recent book Breve historia de Cuba (A Brief History of Cuba), where he explores these ideas.

With the arrival of the 1990s and the loss of the USSR as its main trading partner, the possibility of a Cuban government collapse became a reality. Economist Ricardo Torres, a former researcher at the Center for Cuban Economic Studies and a professor at American University in Washington, explains that at that time, GDP contracted between 35% and 40%, resulting in blackouts, food shortages, and a significant exodus of Cubans. Even so, the government managed to stay afloat until Hugo Chávez emerged in the 2000s as its main ally, sending some 100,000 barrels of oil daily to the island. For the past seven years, Cuba has been experiencing another crisis that has triggered the largest mass exodus in its history. Although GDP has fallen by approximately 15%, Torres sees the current situation — and the threat of losing Venezuelan aid — as unprecedented.

“Industrial production is lower, the deterioration of social services is more severe, along with increased inequality. As a result, society has become much more fractured. Externally, the government has less room to draw on the buffers that worked before, such as foreign investment, remittances, international tourism, or sufficient support commitments from allies like China. This combination of internal crisis and closed-door policies is what makes this crisis existential. Now there is a difference between the terminal crisis of a model and the collapse of the government that sustains it,” Torres insists.

For his part, Rojas believes that Cuba has never been closer to collapse since the Bay of Pigs. “In the 1960s, the country was on the brink of a U.S. Intervention, a civil war, and suffered sabotage, attacks, and an insurrection in the Escambray Mountains, but there was a population boom, industrialization, growing sugar production for the Soviet market, plus all the social measures of the Revolution,” he argues. “Cuba is closer to collapse now precisely because the subsidiary and unproductive model, bequeathed by Fidel Castro, has run its course, and the country has run out of sources of income with which to buy fuel to function.”

Over decades, the Castro regime has created more than 2.4 million exiles, mostly settled in South Florida. While Maduro’s capture at Fort Tiuna clears the path for some, others believe that, after demonstrations like those of July 11, 2021, there is no turning back, and that the end of the regime is inevitable.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.