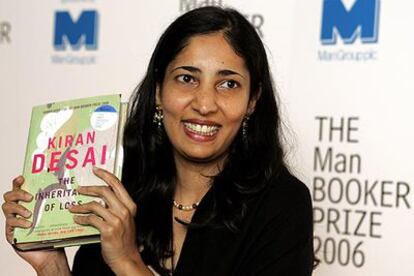

Kiran Desai, the author who disappeared for 20 years: ‘I think of loneliness as sustenance, as shame and as political fear’

The Indian writer, who won the Booker Prize in 2006, discusses her new book, ‘The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny’

On a frigid, sunny morning last December, the living room of Indian novelist Kiran Desai, 54, seemed like the quietest place in New York. That’s quite something: it’s on a street of low-rise houses built in the 1930s in Jackson Heights, Queens, perhaps the busiest area of the city, which is to say, the world; more than 160 languages are spoken here.

She moved before the pandemic, when gentrification — with its “huge skyscrapers and condominiums”— forced her out of Dumbo, Brooklyn. Between the kitchen and the upstairs room, in one corner of which lie part of the 5,000 pages of notes she took while writing it, Desai finished The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny, the monumental, 19th‑century‑style novel she has spent nearly two decades on. In the United States, it was hailed as one of the books of 2025.

Desai — elegant, gentle, and with a mischievous sense of humor — says that the pressure to follow up the phenomenal success of The Inheritance of Loss, which in 2006 made her the youngest woman ever to win the Booker, faded long ago. She doesn’t quite remember when, but she does remember how it gave way to the sheer complexity of the task she had set for herself. “I knew it would be a long book,” she says of a novel she at one point “feared I might never be able to finish.” “I also wanted to have a large cast of characters from different generations, and my decision to approach loneliness from a global perspective — from both Eastern and Western viewpoints — thinking of it as sustenance, as shame, and as political fear.”

The author apologizes for not knowing how to “work any other way.” “I work thematically, the ideas come first, the plot comes much later. It was only in the last couple of years that I had to worry about the plot,” she says. “I envy authors who know the end and work backwards.”

In her case, that ending came when she realized that introducing any changes would have meant altering the entire novel. “That’s the moment you realize that flaws are necessary. That, actually, the most useful thing you have in a book is what’s wrong with it.”

The book The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny follows Sonia, an aspiring novelist, and Sonny, a budding journalist, across years and continents. Both are young Indians whose families regard their American adventure as a mark of status, and both confront the everyday microaggressions against immigrants, the strangeness of displacement, and the loneliness of the new world. The book is also the story of these families, whose family trees greet the reader in the opening pages.

The story takes place in the late 1990s because that was when ‘Indian nationalism burst onto the scene’ — the force that now shapes the country’s destiny under Prime Minister Narendra Modi — and because Desai wanted to explore, through the figure of the grandparents, the “enormous changes experienced by the generation that lived through the transition from British India to independent India.” “My grandfather married when he was 16. The marriage was arranged when he was 16, and my grandmother was 13. She was the second wife because there was such a lot of infant mortality,” explains Desai.

There are more parallels. Like Sonia, she studied in Vermont, with its long winters that test not only one’s patience but also one’s capacity for introspection. She ended up in that corner of the East Coast when her mother — like Sonia’s — defied the conventions of the time and left her husband to take a job as a literature professor, first in the United Kingdom and later in the United States. The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is dedicated to her father who, the author says, “never moved; he was so in love with the landscape.”

Desai, part of the generation that renewed Indian writing in English, is the daughter of the writer Anita Desai, who at 88 lives an hour north of New York. They are very close. When we arrived at her home, the daughter was on the phone dealing with a medical matter concerning her mother. After hanging up, she thanked us for the visit because, she said, it had forced her to dust and bring some order to the “chaos” in the house. She lives alone, though lately, she has had some unwanted guests: “a huge family of large rats in the backyard.”

Her mother, a three‑time Booker finalist, is not only one of her favorite authors (from her work, she recommends Baumgartner’s Bombay, “about her German mother’s experience in India,” and In Custody); she is also her first reader. She grew up watching her write while “raising four children.” “For me, it was easier; I didn’t have to fight to create that rhythm of a writer’s life or the discipline. It felt completely natural to be in the silent home and be working all day.”

Desai has long lived comfortably with solitude, and she enjoys “being obsessed with the news” while staying “far from New York’s literary world.” It was only after moving to the United States that she discovered that the absence of company could also be a physical matter. “In India, there are always lots of people around you,” she explains. “You spend your time trying to find moments for yourself. I’ve never closed a door in India and not had somebody find some excuse to burst in.”

Privacy

That reflection on privacy is shared by Sunny in the novel, when his habits clash with those of his girlfriend from Kansas. At that point, Sonia, who also lives in New York, is caught in a toxic relationship with an artist much older than she is — a self‑important jerk. He advises her not to write about arranged marriages or “orientalist nonsense,” and to avoid “magical realism,” prompting an interesting meditation on what Western readers expect from an Indian writer like Desai.

Feeling insecure, Sonia even replaces guavas with apples in one of her stories — another metafictional wink, since her creator titled her first novel Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard, a satire about a Punjabi man mistaken for a holy figure. And Sonia’s grandparents send a letter proposing an arranged marriage between her and Sunny, which both reject as an outdated custom, even though such unions are still “the majority in India,” according to Desai.

With that bold move by the grandparents begins the zigzagging path of an “Indian love story in a globalized world,” one that takes the characters from New York to New Delhi, from Goa to Venice, and from Paris to Mexico, where Desai spent long stretches while writing the book, trying — “not very successfully,” she admits — to learn Spanish. The writer says she has visited all of those places because, although she has imagination to spare (capable, as The New York Times put it, of writing almost 700 pages without a single one feeling “extraneous or boring”), she believes that “one cannot speak convincingly about places one hasn’t been.”

She also found inspirations for the story closer to home, such as La Gran Uruguaya bakery, a couple of blocks from her home in the middle of the pandemonium of Jackson Heights’ Latin quarter. She took us there to show the advantages — even in slightly below‑zero temperatures — of “living in a neighborhood full of stories just waiting for someone to come and find them.”

In the book, Sunny goes to La Gran Uruguaya bakery and orders a “café con leche” (in Spanish). There, he finally feels comfortable “among people who accept him as another person of color.” Meanwhile, Desai orders a vegetarian empanada at the bakery. Speaking in a voice barely audible over the blare of televisions broadcasting a melodramatic music concert, the conversation drifted to the most famous man of Indian origin in the neighborhood: New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani. The novelist knows his mother, filmmaker Mira Nair, and believes that the proposals with which her son won City Hall are “logical,” given that “the cost of living is insane” in the city.

She also spoke about the paradoxical place the Indian community occupies in Donald Trump’s United States. On one side are the second lady, Usha Vance, and a figure like Vivek Ramaswamy, who ran against Trump in the Republican primaries and now hopes to become governor of Ohio (“what an embarrassment,” says Desai). On the other, the xenophobic nationalism of America First has placed them in the racist crosshairs as the face of the beneficiaries of the H‑1B visa, designed for highly skilled workers. For the MAGA world, they come to steal Americans’ jobs. “Racism toward Indians is growing a lot in this country. I don’t think the community expected this; nor the tariffs,” says Desai, before saying goodbye and heading back to her chosen solitude in what may be the quietest spot in New York.

There, her new literary project awaited her. For now, she is only “playing with ideas,” she said. But one thing is clear: she has no intention of embarking on a literary undertaking as ambitious as the last one. Her readers will be grateful not to have to wait another 20 years.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.