Horden: portraits of family, death, and dreams in an English mining town

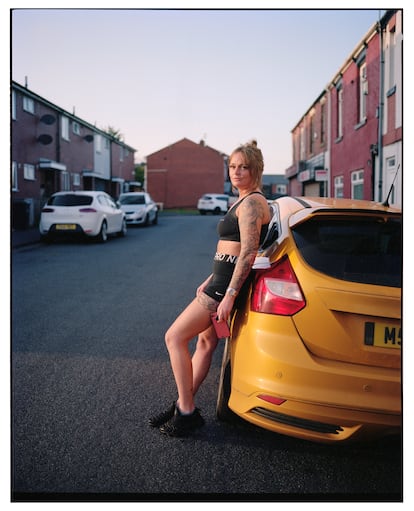

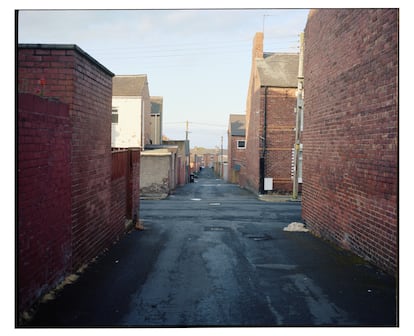

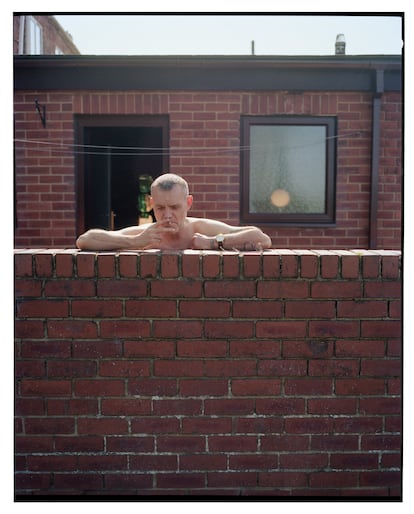

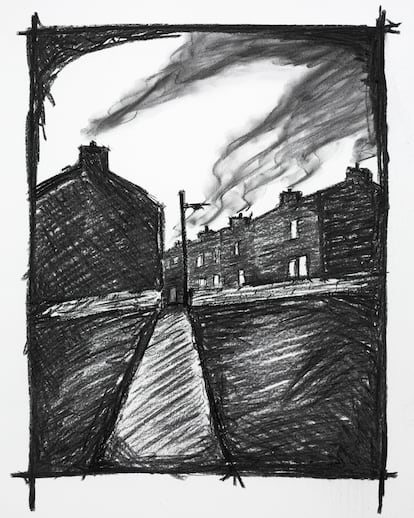

Touching on daydreaming, field research and an oppressive family reality, artist Ed Alcock used photos, drawings and documents to reconstruct the story of his great-uncle Kendon and life in Horden, a mining town in the north of England nestled in one of the poorest areas of Europe

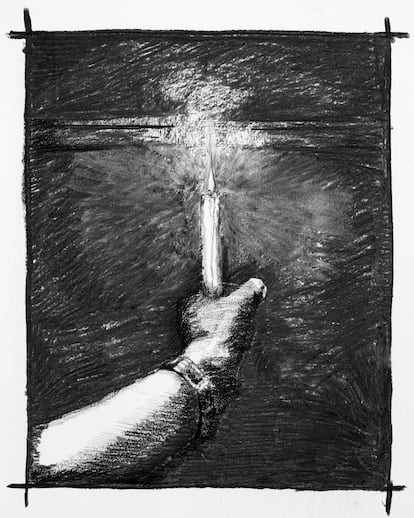

As a child, Ed Alcock listened to the story of his great uncle Kendon’s death at the age of 17. “It happened at the bottom of the mine,” his mother, Sheila, told him one day. “He had been working there since he left school. A section of the gallery sank and a heavy crane fell on him, crushing him and causing head injuries. They took his body out of the mine, but he never regained consciousness.”

Uncle Kendon was an almost mythological figure in Ed’s family, and Horden, the mining town in the north of England where Kendon was born, grew up and died, became a place of legend. Ed’s grandfather – Kendon’s brother and Sheila’s father – moved south years after the accident, but he never stopped talking about it. “For my family, which is a left-wing English family that loves Ken Loach films, Kendon was a working-class hero,” Ed says.

When Britain decided to leave the European Union in 2016, the past resurfaced. By then Ed had been living in Paris for years, first studying mathematics and eventually devoting himself to documentary photography. In the midst of the Brexit process, a grant from the National Center for Plastic Arts took him to Horden. He had never been there, but it was like coming home. It felt distant but also close: part of his identity. What he found was “a town badly hit by poverty, drug addiction, alcohol and mental health problems,” he says. And, at the same time, it had “a great spirit of community, of solidarity and friendship.”

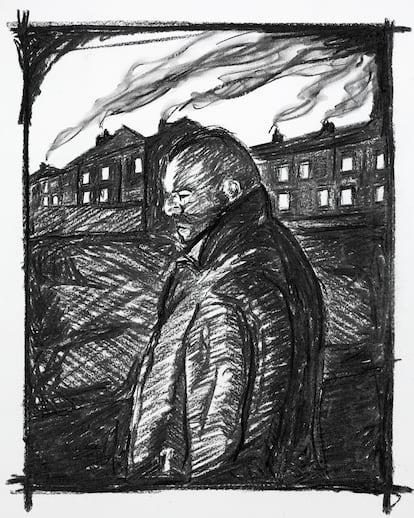

Between 2023 and 2024, Ed travelled four times to this town of 7,000 inhabitants. A region impoverished by the closure of mines in the eighties, it voted in favor of Brexit. On each trip, Ed spent a dozen days in Horden and applied his tried-and-tested method of immersing himself in the place, taking the necessary time, melting into it. He gained the trust of the neighbors and was able to take their portraits. He walked through streets and countryside around the town. He looked through old photo albums. He imagined uncle Kendon and drew him. He found Kendon’s death certificate, which stated that he died of heart failure caused by tuberculosis, not from an accident down the mine.

The result is Buried Treasure, a project that combines the personal with the political. In Ed Alcock’s past work, the personal was the core of Hobbledehoy, a book about his son’s childhood with a text by Emmanuel Carrère. The political aspect is more visible in his reports published in EL PAÍS on France and Germany, or in his exploration of French towns with nuclear power plants. But in Buried Treasure, the personal and political merge. His work is on display until March 29 at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris; and from June 19 in a larger exhibition at the Jeu de Paume in the French city of Tours.

In his work, Alcock examines microcosms of our world that reflect broader realities such as nuclear energy or the abandonment of the old working-class regions. He combines this with personal narrative – his son’s childhood and his family life, the journey to the land of his grandfather and his ancestors. The images of Horden transmit the tragedy of uncle Kendon and also of a mining town hit by economic transformation.

It is a personal story encompassing questions such as where do I come from, who am I? And a universal story, that of communities left behind by globalization to become the breeding ground for the populist wave that has revolutionized half the world. This is the England of the mines and of Brexit, but it could just as easily reflect the industrial north of France and the extreme right of Marine Le Pen, or the Midwest of the United States and Donald Trump. Ed Alcock has gone looking for his roots, and he has found in Horden a painful reflection of our time.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.