Is Heathcliff a narcissist, a madman, a proto-Marxist? The enduring enigma of the ‘Wuthering Heights’ lead character

Jacob Elordi’s performance in Emerald Fennell’s adaptation is the most recent resurgence of a literary figure reimagined so often across film, television, and theater that every generation has cast him as a new man

The faithful admirer. The poisonous narcissist. The erotic icon. The pure-hearted beloved. The depraved necrophile. The Other. The one who walks among us. The proto-Marxist dissident. The idealistic madman. The ruthless psychopath. The powerless victim. Or perhaps their final executioner.

All of these portrayals could apply to Heathcliff, the main male figure in Wuthering Heights, the novel by Emily Brontë released in 1847, just a year before her untimely passing. Its most recent cinematic version, helmed by British director Emerald Fennell and featuring Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi, hits theaters on February 13, and the marketing campaign is already sparking a surge of Heathcliff fever.

But long before Elordi and Robbie stepped into their gothic-romantic performance for the press, Heathcliff had already become one of the most enduring literary figures in the popular consciousness. He is also among the most intricate and paradoxical. Much like other towering novels such as Pride and Prejudice or The Princess of Cléves —and it’s unlikely to be mere chance that all these masterpieces emerged from women writing in times that offered them little welcome—Wuthering Heights has been read in shifting ways across generations, and those readings reveal far more about the eras that produced them—their norms, biases, and anxieties—than about the novel itself.

Casting a quintessential Hollywood sex symbol like Elordi as Heathcliff is both a strength and a flaw. A strength, because the sexual magnetism assumed of someone with such traits effectively conveys the feverish desire he ignites—not just in Cathy, his beloved beyond death, but also in his wife, the ill-fated Isabella Linton. This is true even though the novel never suggests that Cathy and Heathcliff’s passion is ever physically fulfilled—a choice consistent with Victorian-era moral constraints, yet one that deepens the tension in an already volatile atmosphere.

The choice is also justifiable since Elordi has just portrayed Frankenstein’s monster under Guillermo del Toro’s direction, and the two figures exhibit clear similarities. Mary Shelley penned her novel nearly three decades earlier, in 1818, at the beginning of the Romantic era, and her creature symbolized a caution against the distortions that might emerge from an overabundance of Enlightenment rationalism.

Heathcliff, the monster of Wuthering Heights, emerged in the final phase of Romanticism, wielding its irrational and nihilistic power, destined to dismantle the sacred order that had rejected him. Though most of the action unfolds decades prior, in the late 1700s, the character embodies that radical Romantic spirit—in truth, he has been tied to the Byronic hero, inspired by The English poet who was acquainted with Mary Shelley.

But Elordi is also a questionable casting decision—or at least a contentious one—since Heathcliff in the novel possesses a more somber demeanor and is endowed with vaguely defined racial characteristics: he is explicitly described as a “dark‑skinned gypsy” and “that gypsy brat”—it was a different time—who arrives in the port city of Liverpool under equally obscure conditions. This has sparked theories proposing Romani roots, as well as Indian or Jamaican heritage. It is notable that it wasn’t until 2011 that the first Western adaptation of the novel cast a non-white actor: in Andrea Arnold’s version, which underperformed at the box office and received mixed reviews, he was portrayed (very effectively) by Black British actor James Howson.

But it’s also true that Abismos de pasión (1954), the most faithful film version of the novel, directed in Mexico by Luis Buñuel, featured Jorge Mistral, a Spanish heartthrob with dense sideburns and a jaw powerful enough to shatter nuts. Buñuel, like many Surrealists, was captivated by Brontë’s novel, and he emphasized its necrophilic undercurrents and its amour fou dimension, all amplified by Wagner’s mesmerizing score. With its low-budget cast, its erratic, nearly soap-opera-like tone, and its backdrop in the rugged Mexican countryside during the Porfiriato, Abismos de pasión was a bold and groundbreaking film—and for that reason, it honored the source material more than any other adaptation.

Emily Brontë drew inspiration from the Gothic novel, weaving ghost tales and stark landscapes, as she began crafting Wuthering Heights. Upon its release, reviewers responded ambivalently: some lauded its literary depth, yet others condemned it as crude, brutal, corrupt, and overly naturalistic. It achieved modest sales, nowhere near the massive triumph of Jane Eyre, penned by her sister Charlotte and released in the same year (just as Agnes Grey, by their younger sister Anne, was).

Its moment of glory wouldn’t come until well into the 20th century, thanks to advocates such as Virginia Woolf and the influence it exerted on the Surrealists. The book’s reach expanded gradually, until mass culture tamed the tale and cast it as a teenage romantic fantasy, undermining its rebellious essence.

That spirit is strongly evident in the more political readings, which position Heathcliff as a forerunner to Terence Stamp’s character in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s’s art film Teorema. In this interpretation, Heathcliff embodies a time bomb detonated at the core of the bourgeois order that enabled the early Industrial Revolution, which is why he has also been celebrated as a forerunner of Marxist theory (Capital appeared two decades after Wuthering Heights) and as a vehement anti-capitalist avant la lettre.

This demands a brief summary of the story: Heathcliff, a street orphan, is taken in by a country gentleman and brought into his household, where he grows up alongside the man’s rightful heirs—the brooding Hindley, who despises him, and the spirited Catherine, or Cathy, with whom he develops an intense, turbulent connection destined to collapse. Heathcliff later departs from the family, and Cathy wed another local landowner, Edgar Linton.

The runaway will come back as a rich man, consumed by bitterness and resolved to ruin and dismantle that family, yet simultaneously bound by his unbreakable love for Cathy. New passions emerge, accompanied by intense violence, multiple deaths, and a generational shift that most adaptations omit—one that did include it was the 1992 version directed by Peter Kosminsky, featuring a profoundly tormented Ralph Fiennes—even by his own standards—as Heathcliff, alongside Juliette Binoche in the dual role of Cathy and her daughter Catherine Linton. It has remained one of the most fiercely debated adaptations to date. “Ralph Fiennes’ Heathcliff looks admirably unsavoury, though his pained expressions grow monotonous with time, as though he had permanent indigestion,” wrote critic Susan King in the Los Angeles Times.

Moving on to film adaptations, one of the most famous is William Wyler’s 1939 Hollywood masterpiece, where Cathy is portrayed by Merle Oberon—who in reality concealed her Indian roots—and Heathcliff is brought to life by the distinctly British Shakespearean performer Laurence Olivier. Its widespread acclaim significantly reshaped how the work was viewed in the years that followed.

In Truman Capote’s novel Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the protagonist, Holly Golightly, claims to admire Wuthering Heights, but when the narrator understands she means Wyler’s film rather than Brontë’s novel, he responds with a hint of contempt. Hurt, Holly retorts: “Everybody has to feel superior to somebody, but it’s customary to present a little proof before you take that privilege.”

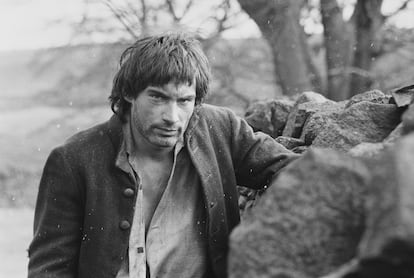

The softening of Heathcliff’s image was also helped along by a widely circulated 1970 television series in which the protagonist was a young Timothy Dalton, who would go on to play James Bond in two films at the end of the following decade.

Prior to that, there had been at least three other TV productions: one from 1958 starring Richard Burton, another from 1962 featuring Keith Michell, and yet another from 1967 with Ian McShane. Similar to Wyler’s film, these television adaptations focused strongly on the story’s romantic framing, a trend echoed in a 2009 miniseries where a very rugged Tom Hardy—with long, silky hair—received the highest acclaim.

The socially bitter outsider, the rebellious rogue, or the broodingly attractive melancholic are all archetypes Heathcliff readily embodies. Figures from literature, theater, and cinema like Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, or George Baines (Harvey Keitel) in Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993) all carry the imprint of his cultural legacy.

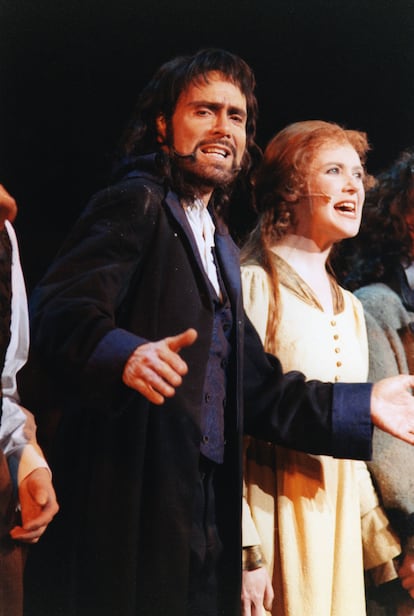

But so too does the rock star archetype—the quintessential rebel insider—whose signature messy, unkempt appearance draws heavily from Emily Brontë’s wild creation: Mick Jagger, Jimi Hendrix, Joey Ramone, and Kurt Cobain all channel him with striking force. The New Romantics of the 1980s, the grunge wave of the 1990s, and their subsequent revivals and reimaginings—particularly the indie scenes of the 2000s—also appear to be cut from the same cloth Brontë stitched in her sole novel. It’s no accident that in the 1996 musical Heathcliff, the lead role was portrayed by rock icon Cliff Richard. And that this template still speaks to younger audiences is evident in the case of musician-actor Mitch, the central figure in Carla Simón’s 2025 film Romería.

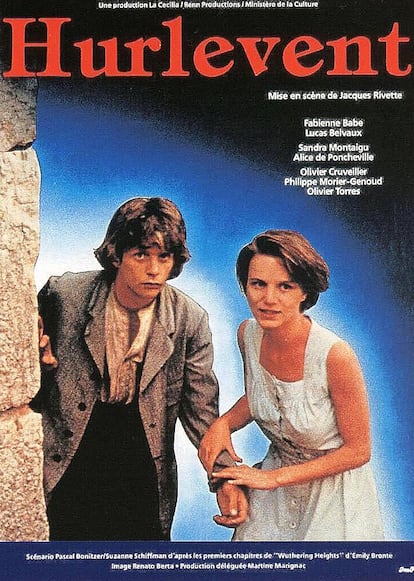

At the opposite extreme is the most stripped-down film adaptation to date: the French-language Hurlevent (1985) by Jacques Rivette, featuring Belgian actor Lucas Belvaux in a markedly subdued performance, devoid of any romantic sheen. There are also more unusual versions filmed in Japan (Yoshishige Yoshida’s adaptation premiered at Cannes in 1988), the Philippines, and India, along with another from 2003 set in modern-day California, which saw barely any release and left no cultural trace whatsoever.

Finally, in one of the most iconic portrayals of the myth in popular culture, Heathcliff never showed up at all. This brings us to 1978, when a then-unknown 19-year-old singer-songwriter, Kate Bush, exploded onto the pop scene with her track Wuthering Heights, paired with an ecstatic and brilliant dance routine that fans still recreate as a homage.

“Heathcliff, it’s me, I’m Cathy, I’ve come home / I’m so cold, let me in your window,” the lyrics said, sung by Bush as a Catherine returned from beyond the grave. Or perhaps she wasn’t only embodying Cathy, but Heathcliff himself, since in the novel the two love each other with such intensity that they merge into a single being. Cathy says this to the maid Nelly in one of the most radical declarations of love in the history of literature: “Nelly, I am Healthcliff! He’s always, always in my mind: not as a pleasure, any more than I am always a pleasure to myself, but as my own being.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción está en uso en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde uno simultáneamente.

Si deseas compartir tu cuenta, actualiza tu suscripción al plan Premium, así podrás incluir a otro usuario. Cada uno iniciará sesión con su propio correo electrónico, lo que les permitirá personalizar su experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

Si no estás seguro de quién está utilizando tu cuenta, te sugerimos actualizar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides seguir compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje aparecerá en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que utiliza tu cuenta de manera permanente, impactando tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.